Predictably, there has been a massive adverse reaction to the news that the UK Government is planning to introduce a compulsory digital national identity card - rumoured to have been dubbed, BritCard. A petition opposing the BritCard has already reached around 1.5 million signatures and social media is seething with indignation and anger. Predictably also, peddlers of dystopian conspiracy theories are having a grand time of it.

As regular readers will be aware, I don’t do knee-jerk reactions. I question everything. I seek and ask the awkward questions. I try to think things through. My reply to the above comment may help to illustrate the point.

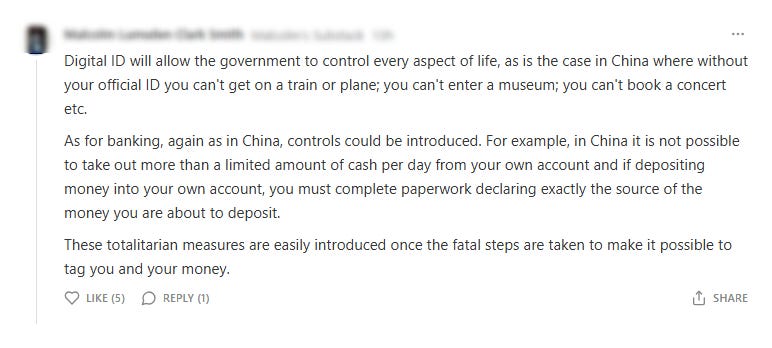

The speculative argument that digital ID will inevitably work in Western democracies the same way as it does in China is fallacious. The political, social, cultural, and legislative contexts are entirely different. The ID system in China was built on structures that were already highly centralised and authoritarian. There were none of the checks and balances that exist in Western democracies. None of the protections for individual privacy. No concept of civil or human rights such as exists in Western culture.

This is not an argument for digital ID. It is merely pointing out serious flaws in a particular line of argument against digital ID. There may be arguments against digital ID that are actually valid. Unfortunately, when conspiracy theories start to roil on social media, concerns for the validity of arguments goes out the window. Shortly to be followed by concerns for veracity and logical cohesion.

Conspiracists compete to tell the scariest story. That imperative tends to squeeze out the concerns and priorities that would otherwise restrain exaggeration and fabrication.

I think it’s safe to say that the default (knee-jerk) judgement on the idea of a digital ID is that it is inherently and entirely a ‘Bad Thing’. I am immediately cautious. Many things are inherently bad. Few things are entirely bad or entirely good. There are a lot of grey areas. Monochrome is common. Duotone is rare. But when a proposal is declared a ‘Bad Thing’, consideration of redeeming features becomes taboo. Discussion of possible positive qualities or aspects is condemned as heresy. My inclination is to react against such constraints on thinking.

When confronted with a proposal such as the compulsory digital ID, my first instinct is to reject it. I hardly need to explain why I would be powerfully averse to anything emblazoned with the offensive Union flag and titled ‘BritCard’. But the ‘compulsory’ part of it also triggers alarm bells in my mind. I have learned, however, that questioning everything means first questioning one’s own assumptions and preconceptions. Doing so, I can find nothing positive about the flag and the name. Anything other than instinctive aversion is not compatible with my Scottish identity or my politics.

Instinctive aversion to ‘compulsory’ is less easy to justify. It is a fact that for civilised human society to be possible, some things must be compulsory. Laws, regulations, rules, and social conventions all have the same purpose - to make the behaviour of others more predictable. Massive and complex human society can only exist and function if individuals are able to predict with a high degree of confidence the behaviour of those with whom they interact.

The law says we must drive on the left so we know with a high degree of certainty that this is what others will do. Imagine driving on roads where motorists were free to choose which side they wanted to drive on. And change their mind at random intervals. The stress would be intolerable. Traffic flow would be impossible. People would be killed. In this case, compulsory is good.

Because there are many such instances where the element of compulsion is necessary and a ‘Good Thing’, we cannot sensibly dismiss out of hand the possibility that the element of compulsion in the case of digital ID is also a ‘Good Thing’, at least in some respects. We need to think about it. We need to defy the taboo and ask the probing questions. We must ask:

Is there a fundamental problem for which digital ID is the optimum solution?

I can immediately think of a problem - or category of problems - for which digital ID might be a solution, even if not the solution.

In a society where people have entitlements which vary between different social groups, it is obviously necessary to be able to distinguish between those who have the entitlement and those who do not. We already do this. I have a card in my wallet which identifies me as a member of a social group - defined by age - which is entitled to free bus travel. Others have cards which identify them as being entitled to operate a motor vehicle on public roads. I do not have such a card. The holder of the driving licence may not be entitled to free bus travel. I am not entitled to operate a motor vehicle because I don’t have the relevant card.

In a society where people have entitlements which vary between different social groups, it is obviously necessary to be able to distinguish between those who have the entitlement and those who do not.

We already use digital ID for a multitude of purposes. In all these instances, digital ID is considered an acceptable solution to the problem of proving entitlement. It enables us to have entitlements which are universal, even if only for defined categories of people.

We also have entitlements which are universal for all citizens and others who have a right of residence. We are all entitled to healthcare services which are free at the point of need. That is probably the most obvious and valued example of the principle of universality being applied. The principle is all but totally universal in the case of healthcare. There are always people who do not enjoy this entitlement even if their presence in the country is perfectly legal - some tourists, for example - as well as those who are ‘undocumented’. Nonetheless, the principle of universality is so rigorously applied in respect of healthcare that the default assumption is always that the person requiring immediate treatment is entitled. The ‘rule’ is, treat first and ask questions later.

We can imagine a society in which there are other entitlements for which the principle of universality is applied just as rigorously. We can, for example, imagine a Universal Basic Income for all citizens. Or a universal right to participate in direct democracy. In these cases, it will be vital to have a secure and reliable means of differentiating between those who are entitled and those who are not.

Modern technology allows information on all these entitlements to be combined in one digital ID. So, the question arises, if it is acceptable to have this information held on a multitude of separate digital IDs, what makes it unacceptable to have it all held in a single digital ID? A question made more pertinent by the fact that the same technology that makes a single digital ID possible is also capable - in principle - of aggregating the information held on many digital IDs. Having the information dispersed does not make it more secure.

It is unarguable that a single digital ID would be more convenient. But such convenience tends to come at a price. So, the question arises as to whether the price of this convenience is too high.

The adverse reaction to the idea of compulsory digital ID revolves around three concerns - privacy, security, and fear of a global plot to ‘track and control’ everybody. (Presumably excepting the ones doing the tracking and controlling. But I can’t be sure of this as I am not familiar with all the details of every conspiracy theory in this area - or any other!)

It is unarguable that a single digital ID would be more convenient. But such convenience tends to come at a price.

Concerns regarding privacy and security already exist with many (most?) of the digital IDs we take for granted. So, the question arises, is the validity of these concerns increased by introducing a single ID? How much of this information really needs to be private? How much of it needs to be secure? How much actually needs to be publicly available and therefore not in any way secure? How much must be confidential and/or secure but readily communicable?

There are a great many questions. Notwithstanding my instinctive aversion to the idea of compulsory digital ID, it is not in my nature to submit to a gut reaction and unthinkingly discount something without having at least some of these questions answered.

Ultimately, it all comes down to one question. What do I gain and lose? It’s a cost-benefit calculation. But that doesn’t mean it’s a simple calculation. And it’s a calculation which will produce different results for every individual. But the result will be fatally distorted if only one side of the calculation is taken into account.

Let me see how good the Govt UK is at going digital? Oh right the NHS COVID-19 contact-tracing app was such a success.

You can be sure the UK digital id will cost billions - remember PPE and probably will never work.

However, I have lived and worked abroad in several countries in Europe and guess what - you need an id card besides your dear British passport.

Indeed, if you are in the likes of the Netherlands, get stopped by the police and cannot produce a passport as a tourist or cannot produce an id card, you do not pass go, you go straight to jail until someone can produce a valid id for you.

Other countries do have immigration problems but they are not in the unholy mess like the UK. The reason why there are so many illegal immigrants is no one kept track of people coming to

the UK until the boat people started arriving or so it seems.

There were hundreds of thousands of illegal immigrants years ago but I don't remember riots.

Perhaps if our Government refrained from bombing countries back to the Stone Age people wouldn't need to come here.

Excellent commentary, Pete. As things stand, there are already vast numbers of people out there with no apparent definitional-line(s) between "private" and "public" regarding their personal behaviour. That aside, the problem isn't i.d. cards, for me the problem is: what will the those who work within the lucrative and ever expanding private security industry do with our information when the politicians come calling on their services. They'll succumb for profit, of course. Regarding the insidious rise of the security industry: who doesn't remember those fairly recent, 'gentler' times when most close-mouths, as a simple example, had no security doors and very few people commented on that fact as being a 'security'problem?